Live-In Relationships vs Marriage in India, a marriage is a formal, legally recognized union (under personal laws like the Hindu Marriage Act or Special Marriage Act) involving solemnization, registration and social status. A live-in relationship means two consenting adults living together without marriage; it has no formal registration or legal ceremony . There is no specific law defining or regulating live-in unions . Courts have repeatedly held that consensual cohabitation by adults is not a crime . The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (DV Act) does acknowledge such partnerships: its Section 2(f) defines a “domestic relationship” to include those “in the nature of marriage” . In practice, this means only live-ins resembling a marriage (see below) receive certain legal protections, but socially and legally a live-in couple remains distinct from a married pair .

Judicial Recognition of Live-In Unions

Indian courts have gradually recognized that long-term, consensual cohabitation warrants legal consideration. In D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal (2010), the Supreme Court laid out conditions for a live-in to be treated as “in the nature of marriage”: the couple must present themselves publicly as spouses, be legally eligible to marry, live together voluntarily for a significant period, and share a household . The Court stressed that brief or casual relationships do not qualify. Likewise, Indra Sarma v. VKV Sarma (2013) affirmed that adults have the right to live together (cohabitation is not illegal) but reiterated that only those meeting the Velusamy criteria can claim marital-like benefits . High Courts, such as in Allahabad, have also protected live-in couples’ rights; for example, a court held that two adults living together gave them privacy and safety under Article 21, and such arrangements are not unlawful . In short, while Indian law does not treat a live-in as equivalent to marriage automatically, the courts have carved out a space where qualifying live-in unions receive certain protections similar to those of spouses .

Also Read: Matrimonial Law in India: Key Considerations for Divorce and Child Custody

Rights of Partners in Live-In Relationships

- Maintenance & Domestic Violence: A woman in a qualifying live-in (one “in the nature of marriage”) can claim maintenance and other reliefs under the DV Act. For example, a 2025 Mumbai magistrate ordered a man to pay monthly maintenance to his ex-partner (and her child), noting that their cohabitation “akin to marriage” justified relief even without a wedding . Under Section 2(f) of the DV Act, a live-in partner is an “aggrieved person” if the relationship meets marriage-like criteria . Thus, victims of abuse in such unions can seek protection orders, residence rights and maintenance under the Act. (By contrast, Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code grants maintenance only to a “wife”, so it generally excludes unmarried partners.)

- Property and Inheritance: Generally, partners have no automatic claim to each other’s assets unless both names appear on the title or there is a private agreement. Inheritance laws do not recognize a live-in partner as a legal heir (unlike a spouse, who is a Class I heir). However, children born of a long-term live-in union are given full legitimacy by the courts. The Supreme Court in Bharatha Matha v. R. Vijaya Renganathan (2009) held that children of live-in parents are not illegitimate if the relationship lasted long, entitling them to inherit from their parents’ estates . (They cannot inherit from the parents’ ancestral Hindu Undivided Family, but they do inherit any parental property.)

- Child Custody: When a live-in relationship ends, custody of children is determined by the child’s welfare. Indian courts do not distinguish between children born in marriage or live-in for custody purposes. Since the law treats long-term live-in children as legitimate , courts award custody and maintenance just as they would for any child. By default, mothers of young children often get custody (as with divorced or widow mothers). The key point is that the child’s right to parental support continues regardless of the parents’ marital status.

Also Read: All About Family Law in India: Understanding Your Rights

How Rights Differ from Married Couples

- Maintenance: A married wife can claim maintenance under CrPC Section 125 as a “wife”; a live-in partner can claim it only via the DV Act if her union qualifies as marriage-like . In practice, this means married women have a direct statutory right, while live-in partners rely on judicial interpretation. (Similarly, a husband’s maintenance rights in a live-in are unclear.)

- Succession: A surviving spouse is an automatic heir under inheritance laws; a live-in partner has no such status. Inherited property by marriage flows to the spouse, but partners must make wills or other arrangements to pass assets.

- Legal Formalities: Married couples have rights and duties enshrined in various laws (divorce/maintenance under family law, widow pension, nominee status for insurance/visas, etc.). None of these automatically apply to live-in partners. For example, a married person can seek alimony on divorce; there is no legal process for “separating” a live-in.

- Social Security and Recognition: Only a spouse is recognized for legal benefits (joint filing of taxes, family health insurance, adoption by couples, etc.). A live-in partner may not be recognized as “next of kin” in hospitals or for visas. In short, marriage confers many legal statuses that cohabitation does not.

- Children’s Legitimacy: In marriage, children are by default legitimate heirs. In live-ins, children attain legitimacy by judicial protection (as above). Custody and maintenance rights for the child are the same in either case, once paternity/maternity are established .

Landmark Judgments and Recent Trends

- 2010 (D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal): The Supreme Court laid down the test for a live-in to be “in the nature of marriage” , providing a landmark framework for later cases.

- 2013 (Indra Sarma v. VKV Sarma): The Court held that while adults are free to cohabit, relief under the DV Act only applies if the relationship meets Velusamy’s conditions .

- 2009 (Bharatha Matha v. R. Vijaya Renganathan): The Court ruled that children of long-term live-in parents are not illegitimate, and granted them inheritance rights .

- 2024 (High Courts and Legislation): In Madhya Pradesh, a High Court held that a long cohabitation can create a presumption of marriage for maintenance purposes, allowing a live-in partner to claim support under Section 125 CrPC . In Uttarakhand, the new civil code controversially proposed mandatory registration of live-in relationships (seen by critics as intrusive).

- 2025 (Supreme Court and lower courts): The Supreme Court observed in May 2025 that a prolonged live-in cohabitation implies mutual consent, making promises of marriage less credible in rape cases . Also, a Mumbai magistrate recently ordered a former live-in partner to pay maintenance, underscoring that courts will impose financial responsibilities in such unions . These decisions reflect a trend towards recognizing the real-life dynamics of cohabiting couples.

Challenges and Gray Areas

The biggest issue is legal uncertainty. There is no codified law on live-in relationships, so courts “fill the vacuum” case by case . This leads to inconsistent outcomes. For instance, some courts require very strict proof of a marriage-like relationship, while others focus on fairness and protection. States like Uttarakhand have even tried to regulate live-ins by law , raising debates about privacy and state power. Other gray areas include spousal inheritance (e.g. can a live-in partner claim a share in ancestral property?), police harassment (sometimes families allege kidnapping, even when both are adults), and how personal laws (like Muslim law on marriage) apply or not. Courts continue to expand protections under existing laws (e.g. broadening “wife” for maintenance ), but the lack of clear legislation means many questions remain open.

Also Read: Alimony and Maintenance: What They Mean in 2025

Social vs Legal Acceptance

Social attitudes towards live-in relationships vary widely. In big cities, cohabitation is increasingly common, while in rural or conservative communities it remains stigmatized. Legally, however, courts have affirmed that adults have a right to choose their partner. The Allahabad High Court explicitly protected an adult couple’s privacy and Article 21 right to live together . The Supreme Court has likewise emphasized personal liberty and privacy in relationships (e.g. in cases upholding consensual adult sexuality). Nonetheless, proposals like mandatory registration underscore social tensions. Critics of such laws note that while registration might aid women’s claims, it “undermines the very idea of live-in relationships” as a choice to avoid commitment . In essence, Indian law is gradually recognizing live-ins as a fact of life, but social acceptance lags in many quarters.

Precautions for Live-In Couples

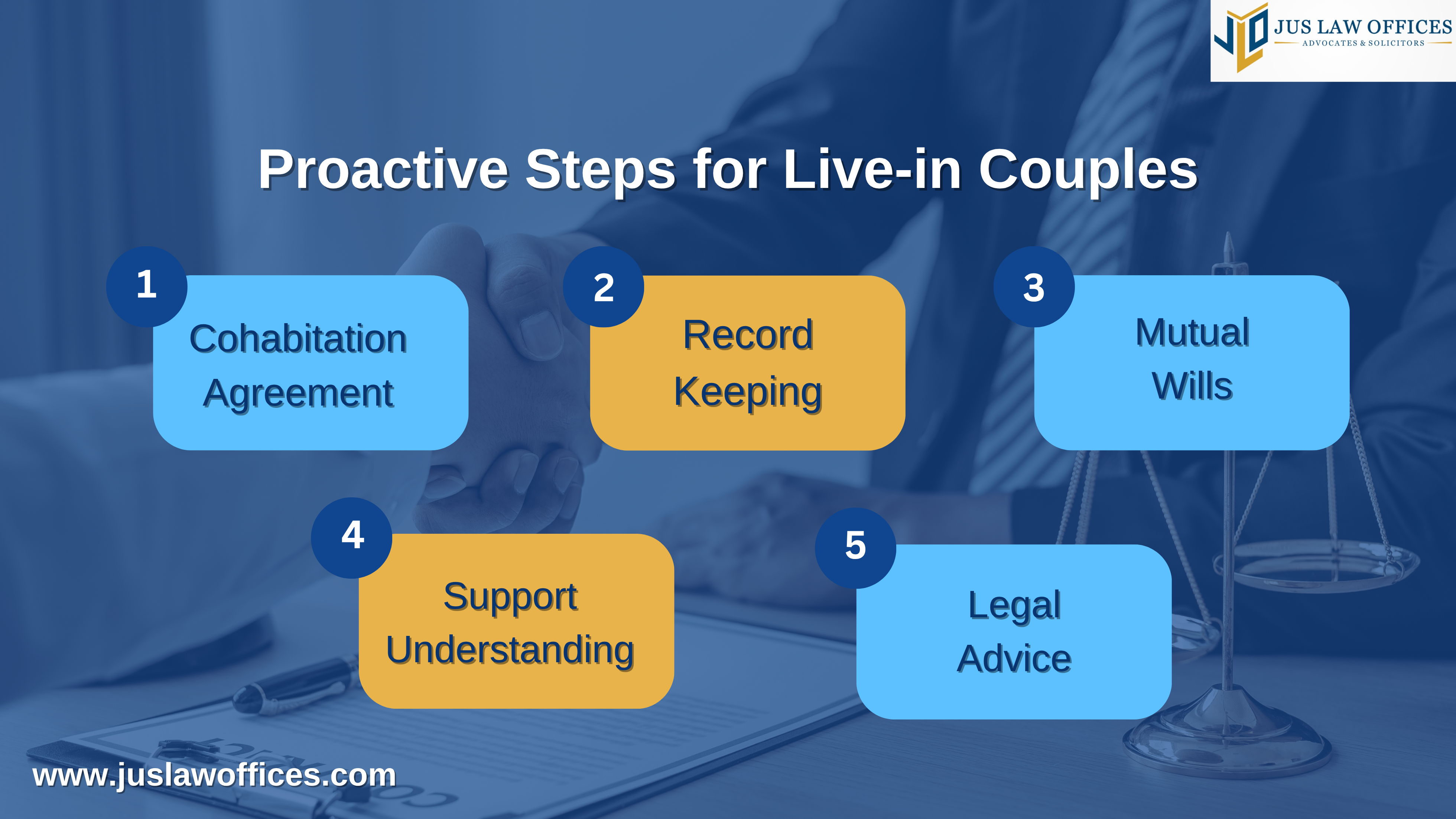

Because rights are neither automatic nor uniform, couples often take proactive steps:

- Cohabitation Agreement: Consider a written agreement (not legally required but evidential) spelling out shared expenses, property ownership, and financial support.

- Record-Keeping: Maintain clear records of joint leases, bills, bank accounts or investments. Documentation can prove the extent of your partnership or contributions if disputes arise.

- Mutual Wills: Each partner can make a will naming the other as beneficiary, ensuring inheritance if one dies without issue. Otherwise, the surviving partner may have no legal claim.

- Support Understanding: Be aware that a child born to you will have full rights to support and inheritance (like any legitimate child) , and discuss financial arrangements accordingly.

- Legal Advice: Seek guidance from a lawyer to understand liabilities (for example, a partner may be expected to maintain the other and any children under the DV Act) and to handle issues like custody or rent agreements.

By taking such precautions, couples can better protect their interests within the present legal framework.

Sources: Authoritative court judgments, legal analyses, and recent news reports provide the basis for this summary.