Separation and divorce are emotionally tough, and money worries add stress. In India, “maintenance” (often called alimony) is court-ordered support one spouse pays to the other after separation. Broadly, alimony usually refers to a post‑divorce award (often a lump sum or fixed payments), whereas maintenance covers both interim support during proceedings and post-divorce support . Both ensure that a financially weaker spouse can meet basic needs after marriage breaks down. Indian law tends to use these terms interchangeably, but a practical distinction is that maintenance can be granted before the divorce is final (pendente lite), while alimony often denotes permanent support after a divorce decree.

Laws That Govern Spousal Support in India

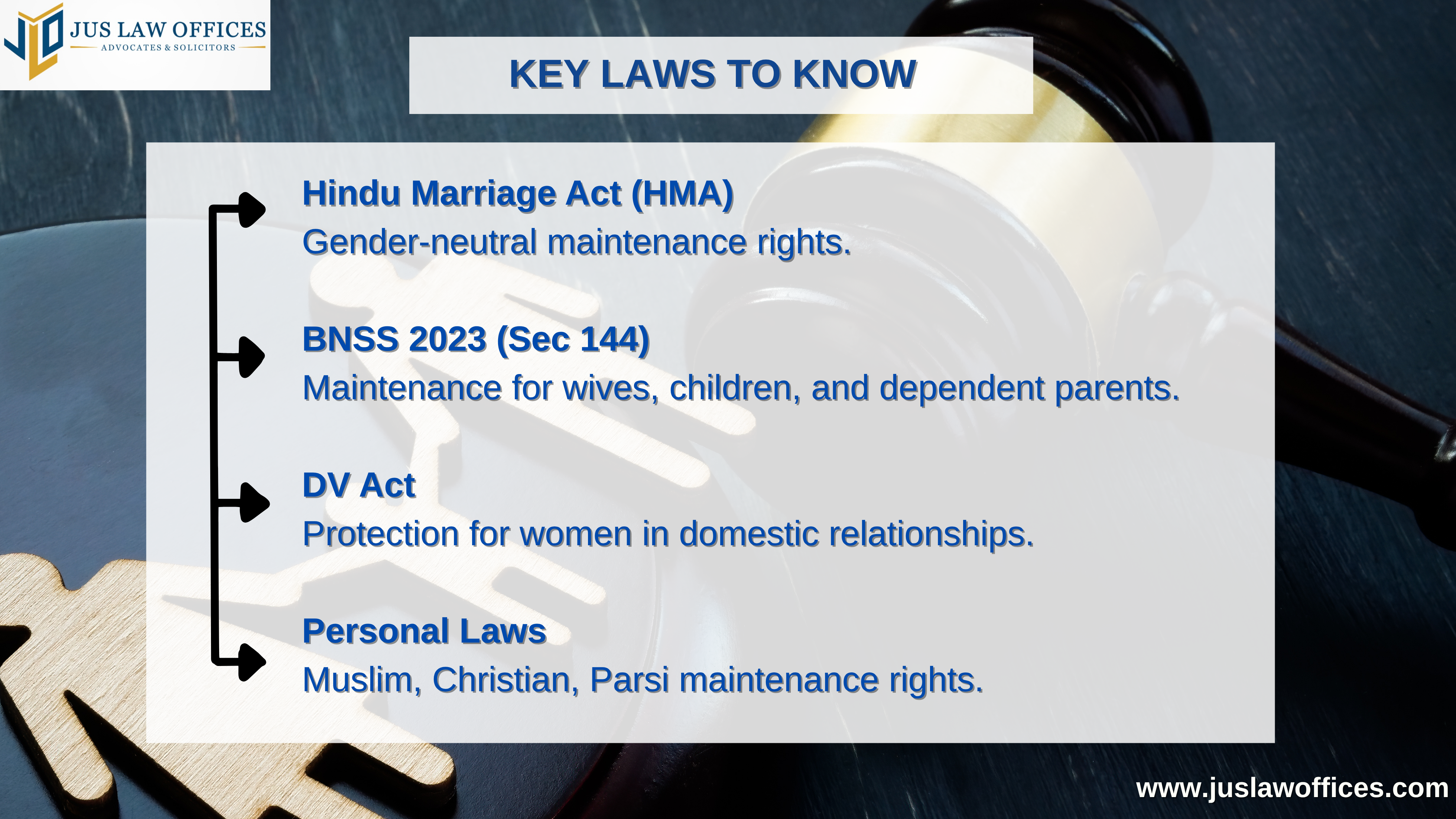

Financial support for a spouse is governed by several laws – personal (religious) laws and secular statutes – which often overlap. Key provisions include:

- Hindu Law: Under the Hindu Marriage Act (HMA) and Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (HAMA), a wife can claim maintenance if deserted or neglected. HMA Sections 24‑25 allow pendent‑lite (during the case) and permanent maintenance or alimony . (Interestingly, HMA is gender-neutral: a “deserving” husband without means may claim support from his wife if she can pay .)

- Special Marriage Act (SMA): For inter-faith or other marriages, SMA Sections 36‑37 mirror the HMA, providing pendente-lite and permanent alimony.

- Secular/Criminal Law (BNSS 2023): Previously Section 125 of the CrPC, now Section 144 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (effective Dec 2023), allows a Magistrate to order maintenance of wives (including divorced, non‑remarried wives), children, and dependent parents . This covers all faiths equally.

- Domestic Violence Act (2005): Any woman in a “domestic relationship” (including a live-in partner) can seek maintenance under Section 20 of the DV Act, which operates alongside the above laws.

- Other Personal Laws: Muslim women (under Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986) and Christian/Parsi spouses (under the Indian Divorce Act and Parsi Marriage Act) also have similar maintenance provisions.

Each law has its own procedure, but multiple remedies can be invoked. For example, a Hindu wife could claim under HMA, HAMA and the BNSS separately, though courts may offset overlapping orders to avoid undue burden on the payer . Overall, these laws aim to prevent destitution by ensuring a needy spouse can get support .

Also Read: All About Family Law in India: Understanding Your Rights

How Courts Calculate Support (Amount & Duration)

Courts do not apply a fixed formula. Instead, they look at the specific facts of each case. Key considerations include:

- Income, Assets and Earning Capacity: The court compares both spouses’ resources – salaries, property, investments, business income, etc. A spouse with ample means is expected to support one with little or no income.

- Standard of Living: The aim is often to let the dependent spouse maintain a lifestyle comparable to the marriage. If the couple lived comfortably, maintenance must reflect that dignity. The Supreme Court has noted that maintenance should be “sufficient to ensure [the] woman lived with dignity after separating”.

- Length of Marriage: Longer marriages usually mean greater entitlements, since long-term spouses are often more dependent. Very short marriages may produce smaller awards.

- Age and Health: Older or unwell spouses who cannot earn easily generally receive higher awards. A young, healthy spouse is expected to become self-sufficient sooner.

- Children and Dependents: If the recipient spouse has custody of children, support may be higher to cover childcare and schooling. Child maintenance is separate but can affect spousal maintenance orders.

- Contribution to Marriage: Non‑monetary contributions (homemaking, child care, etc.) are recognized. Courts often factor in if one spouse sacrificed career prospects.

- Conduct of Parties: Serious misconduct (like proven cruelty or desertion by one spouse) can tilt orders in favor of the wronged spouse. In no-fault divorces (mutual consent), financial need is the main factor.

In practice, a useful benchmark cited by the Supreme Court (2017) is that roughly 20–25% of the husband’s net income can form a “just and proper” alimony amount, subject to adjustment . For example, if a husband earns ₹100,000 per month, a maintenance award around ₹20,000–25,000 might be deemed fair to support his former wife and child in comfort. However, the Court stressed this is not a rigid rule – the judge “moulds” the award to be just in each case .

Once set, permanent maintenance typically runs for life (or until the receiving spouse remarries). Under family laws, courts may modify or end awards if circumstances change. For instance, if the dependent spouse remarries, maintenance usually ceases. If the payer’s income drastically falls (e.g. job loss), courts can reduce or suspend payments . (Victims of domestic violence are protected similarly: a live-in partner who qualifies under DV Act is entitled to maintenance until she remarries or the court orders otherwise.)

Also Read: Matrimonial Law in India: Key Considerations for Divorce and Child Custody

Gender-Neutrality and Recent Trends

Historically, maintenance laws were viewed as for women’s benefit, since wives traditionally had fewer earning prospects. In recent years, society and some judges have called for gender-neutral support – arguing any spouse (husband or wife) should be able to claim if needy. Hindu law is already gender-neutral in wording (either spouse can apply under HMA Sec 24/25) and courts have granted husbands maintenance in some cases . For example, a “deserving husband” without income but whose wife has means can seek pendente-lite or final alimony .

Nevertheless, the prevalent trend is still protection of women. The Supreme Court recently reiterated that maintenance is rooted in social justice for wives and children . In April 2025, the Court refused to rewrite maintenance law, dismissing a PIL to make Section 125 (now 144 BNSS) gender-neutral. The bench asked, “Tell us which provisions are not being misused?” and noted that any change must come from Parliament . In practice, husbands’ claims (under HMA or CrPC) succeed only if he truly lacks means and his wife can pay. Most maintenance awards are to wives; courts assume wives to be “vulnerable” spouses unless clear evidence says otherwise .

Impact of the New BNSS (2023)

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, which replaced much of the CrPC, largely codifies Section 125’s maintenance rules. Section 144 BNSS requires a Magistrate to order maintenance if a person “with sufficient means” neglects his wife (unable to maintain herself), minor child, or dependent parent . Notable points in BNSS 2023:

- Procedural timelines: The code adds strict deadlines. For example, interim maintenance applications must, as far as possible, be disposed of within 60 days of notice . This aims to speed up relief.

- Scope: The definitions remain the same. The term “wife” explicitly includes a woman divorced from her husband who has not remarried . Wives living separately by consent or in adultery can be denied maintenance (per Section 144(4)–(5), mirroring old law).

- Enforcement: BNSS retains the strong enforcement provisions. If a defaulter ignores the order, the court can issue a warrant to levy (seize) the amount and even send him to civil jail for up to one month (or until payment) . In short, non-payment can mean wage‑garnishment, property attachment or brief imprisonment.

- Unchanged Elements: Otherwise, Sec144 is almost identical to old Sec125 CrPC. The intent is still to relieve indigent wives/children/parents, and remedies (interim maintenance, expenses of proceedings) are the same as before.

In summary, the BNSS tweak was mostly procedural: faster disposal and a new section number, but no watering-down of maintenance rights for wives.

Rights of Husbands, Wives and Live-in Partners

- Wives: An Indian wife generally has a strong right to maintenance. Whether Hindu, Muslim, Christian, etc., a wife unable to support herself can claim maintenance during the marriage or after divorce under her personal law and/or Sec 144 BNSS. Courts will protect a wife from destitution, provided she herself has behaved properly (i.e. no adultery or unjust refusal to live with her husband). A divorced wife also qualifies under BNSS as noted above.

- Husbands: A husband’s right to claim maintenance is more limited. Under Hindu and secular marriage laws, a “deserving husband” without income may apply (for example, HMA Sec24 allows him to claim expenses of court proceedings; Sec25 allows permanent maintenance by his wife ). Similarly, the Indian Divorce Act has provisions for a needy husband. However, successful claims by husbands are rare; courts focus on his actual inability to earn and consider whether the wife has independent means. Recent discussions on gender-neutral maintenance show that husbands sometimes raise legitimate needs, but as of 2025 the law still emphasizes wives’ protection.

- Live-in Partners: Women in a live-in relationship (unmarried but cohabiting “like spouses”) can seek maintenance under the Domestic Violence Act. The Supreme Court has held that to qualify, the couple must have held themselves out as husband and wife, lived together for a significant period, pooled finances, etc. (the Velusamy/Indra Sarma tests) . If those conditions are met, the woman is treated as an aggrieved spouse and can get maintenance for herself and her children under Section 20 of the DV Act. (Men in live-in relationships have no corresponding maintenance remedy.) For couples not meeting the marriage-like criteria, no maintenance award is available unless they actually marry.

Tax Treatment of Maintenance in 2025

For the payer: Alimony/maintenance payments are treated as personal expenses. Neither periodic payments nor lump-sum alimony are tax-deductible under Indian law . In other words, paying spouse gets no income-tax break for these payments.

For the recipient: The tax position depends on how support is structured. A one-time lump-sum payment in lieu of maintenance is usually treated as a capital receipt and not taxed . However, regular alimony paid monthly or annually is counted as the recipient’s income (under “Income from Other Sources”) and is taxable . (This means a divorced wife receiving ₹20,000 per month must include that in her taxable income, while a lump-sum award is tax-free.)

These rules have not changed recently. It’s important for spouses to report and plan accordingly. If support is paid via property transfer, normal gift-tax rules apply: pre-divorce gifts from relatives are exempt, but post-divorce transfers (between ex-spouses) may be taxable if large .

Enforcement and Penalties for Non-Payment

Courts take non-payment of maintenance very seriously and have several enforcement tools:

- Wage or Asset Attachment: If payments stop, the recipient can move the magistrate to enforce the order. The court can issue a warrant to attach the defaulter’s bank accounts, income (garnish salary/pension), or other assets to recover arrears . For example, the husband’s employer can be directed to deduct a fixed portion of salary and pay it directly to the wife or children. If the husband owns property (house, land, vehicles), the court may freeze and even order sale of those assets to satisfy the debt .

- Warrant for Recovery: Under BNSS Section 144(3), the Magistrate can issue a warrant “for levying the amount due in the manner provided for levying fines” . This typically involves seizing and selling assets or forcibly collecting the dues.

- Imprisonment for Default: If attachment fails, the court can go further. After two breaches of the order, the magistrate must issue a civil arrest warrant. The defaulter can be jailed up to one month or until the sum is paid, whichever is earlier . Crucially, this is not punitive jail time for a criminal offense – it is civil imprisonment for contempt of the support order. Once released, the obligation remains. In short, a defaulter risks losing freedom briefly unless he clears the maintenance.

These powers are powerful levers to ensure support is paid. In practice, many defaulting spouses settle the debt once they face attachment or jail. But if a paying spouse genuinely can’t pay, they should apply to vary the order rather than simply ignore it.

Seeking and Modifying Maintenance Orders

- How to Apply: A spouse seeking maintenance should file the appropriate petition as soon as separation occurs. Hindu and secular spouses apply in Family Court (under HMA/SMA), while any spouse can apply to a Magistrate under BNSS Section 144 (CrPC 125). Domestic violence cases go to the Magistrate under the DV Act. Courts generally allow interim maintenance (pendente lite) to cover living expenses while the case is pending, and a final order at divorce or trial.

- Gather Evidence: Full financial disclosure is key. Courts expect each party to submit an affidavit of assets and liabilities (listing income, bank balance, property, debts, etc.). The Supreme Court has even directed husbands in high‑profile cases to file years of income tax returns, bank statements, and passport copies when appealing maintenance orders . Being transparent about finances helps the court make a fair award.

- Negotiation and Mediation: Spouses often settle support via mutual agreement. An amicable settlement – drafted into a separation agreement – can save time, cost, and emotional strain. Mediation through a neutral mediator or family counselor is encouraged. If both agree, the court will usually approve a reasonable negotiated amount. If not settled, the court decides on evidence.

- Modifying Orders: If circumstances change later, either side can ask the court to modify or stop the payments. Key situations include: the recipient spouse remarries (maintenance generally ends) or begins earning sufficiently, or the payer loses income or is facing hardship. Family courts routinely entertain variation petitions. For example, if the payer’s salary is drastically cut, he can petition to reduce the amount. Conversely, if the payee’s needs increase (major illness) she can ask for more.

Current guidance reminds parties to be fair: orders can be changed only by court approval. One commentator notes: “A wife who remarries should not continue to get maintenance, and if a husband cannot pay after losing his job, the court will reassess the situation” . In any case, do not stop or withhold payments without court permission—continue paying interim dues or file a modification petition.

Takeaways for Separated Couples

- Know Your Rights: You are entitled to ask for fair maintenance or alimony according to law. Wives have a strong right to support under multiple statutes; husbands have limited rights under personal law. Live-in partners (women) can also seek support if the relationship resembles marriage .

- Act Promptly: Do not delay in filing. The law favors early application (interim orders can be quick). If you wait too long, courts may consider the delay. Also, be prepared with detailed financial documents to back your claim.

- Be Reasonable and Honest: Courts expect honesty in disclosing income and expenses. Exaggerating needs or hiding assets can backfire. Remember that maintenance is intended to meet basic living standards, not to punish one spouse or unduly enrich the other.

- Seek Professional Help: Family law can be complex. A lawyer or legal aid clinic can guide you through procedures, documentation, and negotiations. Lawyers often facilitate mediated settlements which are quicker and less adversarial.

- Stay Flexible: Understand that maintenance orders can change if your life changes. Communicate with the court if your job status or marital status changes. The law allows modification, so long as the process is followed legally.

- Know Enforcement is Serious: If you win a maintenance order, know the court will enforce it vigorously. Conversely, if you’ve been ordered to pay, ignoring it can lead to wage garnishment, fines or even brief jail time . Always comply or seek legal modification in the event of genuine hardship.

Spousal support laws are evolving but remain focused on fairness. Courts in 2025 balance the documented needs of the weaker spouse against the payer’s ability, aiming to preserve dignity for both. Understanding these rules—now updated under the new codes—will help you navigate separation with confidence and protect your financial future.

Sources: Relevant statutes and recent case law (as of 2025) have been consulted, including the BNSS 2023, Supreme Court guidelines (e.g. Rajnesh v. Neha, 2020), and authoritative legal analyses . (Legal counsel should be sought for advice on specific cases.)